George Whitty on Influential Jazz Piano Players: Part 2

Herbie Hancock

Here we have somebody who I would say is probably the most influential pianist of the last 50 years, and one of our all-time most extraordinary musicians.

Everything that came before him, from the jazz world to the classical world, all came together and then got kicked up several quantum leaps in Herbie’s hands. He was a child prodigy, playing with the Chicago Symphony at the age of 11, and didn’t get into jazz until early in high school, but ouch, the way he took to it from there.

Playing with people like Donald Byrd and Oliver Nelson shortly after turning 20, he joined Miles Davis’s quintet at the age of 23. Which is pretty ridiculous considering the wealth of piano talent that was out there. But right from the very start you hear that this is something incredibly special.

I’ve often thought that Herbie is the ultimate expression of the human potential:

Unbelievable real-time mental facility, incredible physical dexterity that manifests more often than not with the most exquisite touch in the history of the piano, and a huge dose of what’s best about the human soul. All expressed by the most potent medium we have: music.

The depth of Herbie’s harmony is truly second to none, his way of laying the notes in there is something that’s often imitated but has never been duplicated. An incredible study in time, effortlessly swinging, always singing and always supported by Herbie-Only Harmony®.

A lot of what makes his playing work so beautifully, and makes it so hard to imitate, is that touch. Herbie’s chords are often full of little buzz-notes that have to be laid in just so, maybe a little later than the rest of the chord, sometimes almost inaudible, all 10 fingers on their own little trip articulating things just so.

I know he was intrigued by the Hi-Los, the great vocal group with Claire Fischer and Gene Puerling doing the arranging; maybe that had something to do with it, 4 separate voices all doing their thing. Whatever it is, it is an instantly identifiable sound.

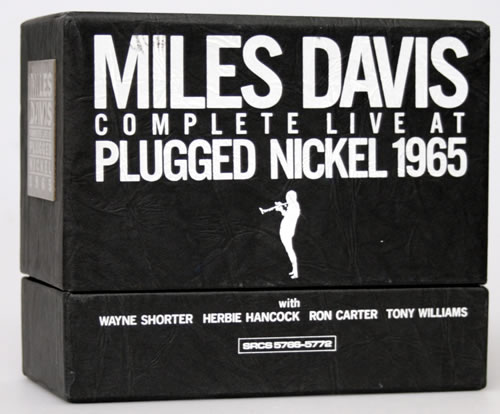

The other thing that really distinguishes Herbie is the way he accompanies a soloist. I highly recommend a box set called Miles Davis at the Plugged Nickel, which I think was made in 1965. It captures an exceptionally spacious era in that band’s development and has a very cool “jazz club” sound to it to boot. But check out the interplay; Herbie so often just waits until Miles or Wayne is finished with their phrase, and then just drops in a little thought, one cooler than the next.

Can’t say enough about the guy; I’ve been fortunate to be able to work with him for the last few years.

One project I worked on was doing orchestral arrangements for him and Wayne Shorter, orchestrating some duo concerts they did 15 years or so ago. And the duo concerts are just insanely great, totally improvised (often you don’t even figure out what tune it is until well into the performance).

And I asked him one day “So did you and Wayne used to do this sort of thing at sound check with Miles?” And he said “Oh, no, we could never have done this sort of thing back then…”. Which, considering how incredible they were back then, says a LOT.

Herbie is also a Nicherin Buddhist (and he got me into this as well), a practice in which we chant a couple times a day, some of the function of which is to focus on where we’d like to go, what we’d like to do. One night in Calgary we were chanting before a performance and I asked Herbie what he chanted for.

And that night, he said “I chant that the audience has a good time, and that the audience and I are one”.

Think on that. Or better yet, put on any of Herbie’s CDs and you can hear that spirit and that generosity for yourself, clear as a bell.

McCoy Tyner

This is another of the 4 guys who most shaped my approach to playing piano. And another one who’s defined by inventing a huge part of the jazz vocabulary EVERYBODY uses, and in a most ingenious response to a saxophonist who was so treading the outer limits that an entirely new way of accompanying him had to be invented: John Coltrane.

My friend Dean Brown points out something about McCoy Tyner: he’s quite possibly the most intense jazz pianist ever, but everything, even at its most intense, still sounds JOYFUL in a way.

Not that he can’t play a ballad that will make you cry, too, but his playing is THRILLING and exhilarating, not dark and foreboding despite a large dose of powerfully played dissonance. And a lot of that has everything to do with the fact that he’s an incredibly swinging pianist in addition to the stellar chops and the brilliant ideas.

Check out a disc called McCoy Plays Ellington, and put on his version of “In My Solitude”, and you’ll instantly hear what I mean.

We get into some of McCoy’s harmonic techniques toward the end of the jazz piano lessons here on ArtistWorks; what he basically did was take some ideas that Red Garland and a couple other pianists had been working with and develop it into an entire harmonic language that let him get up and under John Coltrane without conflicting with what he was doing.

As we discuss in that part of the lessons, a soloist like that doesn’t want to have to conform to your choice of harmony, your idea of what the extensions on the chord should be, and so forth.

McCoy really developed the “quartile harmony” that everyone since has employed at least some (Chick Corea was clearly influenced by this, as was the brilliant pianist Kenny Kirkland, Joey Calderazzo as well), which has a big, open, almost strumming sound and which can easily be adapted to go where the soloist goes. And it’s incredible to hear him playing with Trane or just letting it fly on his own trio gigs.

And ALWAYS, ALWAYS swinging.

I once saw him play a gig at a club in Harvard Square with his quartet, and by the break he had pounded the piano flat out of tune and there was a tuner up there in the middle of this horrific din of everybody drinking and carrying on trying to pull it back into tune. But McCoy had done that swinging EVERY SINGLE NOTE with that exuberance that I so associate with him. Gary Bartz was also on fire on saxophone that night, but that’s another story.

DON’T MISS IT if you get a chance to see McCoy Tyner play; this is one of the tiny handful of true titans.

And if he’s working with Al Foster, drive 500 miles if need be.

Thelonious Monk

What a unique gift this guy had, and what a way of really cranking open the jazz vocabulary.

No “standards” here, he, like Charles Mingus as well, was going to create entirely original, fresh music PERIOD. And in that sense, he was truly one of the “most jazz” of jazz musicians: everything ought to be different every night.

Mike and Randy Brecker, I’ve always thought, had a lot of Monk in them. If things were too consonant, if there was nothing pricking your ear with some piece of fresh harmony or a turn of phrase that made you laugh, it’s too boring, too vanilla, too thin. EVERY note the guy played was weighted with a very specific twist to it.

With the time, with the choice of notes, with the way he accented, the entire thing has a way of forcing you to listen. It’s kind of the opposite of driving on a freeway, where you get into gear and enjoy that it’s a cruise. Monk’s playing is a twisty mountain road that’s a hell of a lot of fun to drive. His pieces are still played constantly on stages around the world, but few people really try to play them like this great original did.

Sometimes I wonder if the great guitarist John Scofield listened a lot to Monk; often he’ll really buzz up his playing by, for example, harmonizing his melody note a major 7th down. Thelonius Monk was constantly experimenting with this kind of thing, probing the outer reaches of how harmony could work, how it could shade the melody he was playing, and what kind of interesting tunes he could make out of it.

The “European” harmony book? Totally out the window, and in its place an entirely new, ingenious way of thinking.

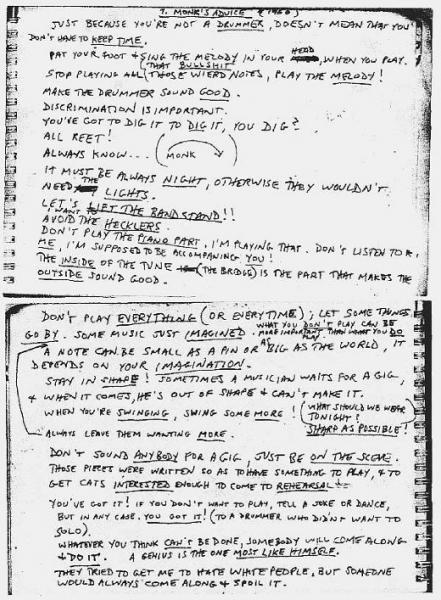

For a really great read also that’s a cool window into a truly original thinker, check this link which contains a full transcription of Monk's handwritten advice to anyone playing with him. Pure genius:

The whole list is a true gem, almost like Cliff’s Notes on how to be a good jazz musician. Here are couple good ones from it:

- “Don’t play all those weird notes, PLAY THE MELODY!”

- “If you’re swinging, swing some more!”

- “Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that! I’m supposed to be accompanying YOU!”

Stay tuned for more in Part 3!

Related Blogs:

- Jazz Piano Lessons with George Whitty Now Available

- George Whitty on Influential Jazz Piano Players: Part 3

- George Whitty on Influential Jazz Piano Players: Part 1

- Jazz Piano Lessons with George Whitty Coming Soon

Learn Jazz Piano Online with George Whitty at http://artistworks.com/jazz-piano

Comments